Breadcrumb

- Home

- About

- Iowa Geode Stars

- P.B. King

P.B. King (1903-1987)

P.B. King - with Emphasis on the Iowa City Years

By Bill Raatz

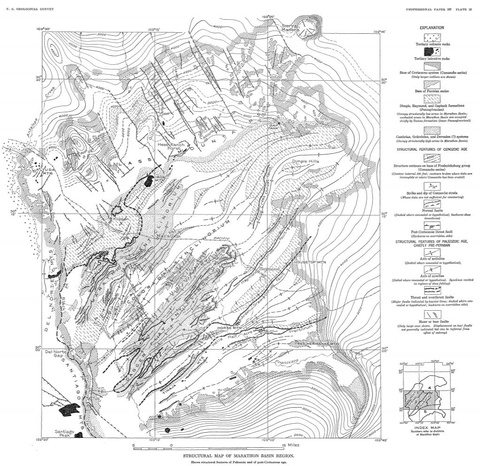

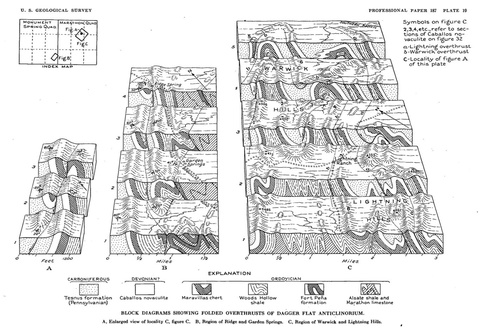

Philip Burke King (1903-1987; University of Iowa BS ‘24, MS ‘27) was one of the great geologic mappers of the 20th century, spending most of his career with the USGS where he published works of such insight that they remain the gold standard today. His West Texas publications covering the Marathon Basin, Glass Mountains, Sierra Diablos, Hueco Mountains, and Guadalupe Mountains are venerated for their detailed geologic interpretations, accuracy of mapping, and elegant hand-drawn illustrations. The Permian Basin region is one of the most intensely studied areas on Earth, due to its economic importance as an oil and gas province, and as an outdoor laboratory for examination of complex shelf to basin mixed carbonate clastic depositional systems. King’s work created the foundation for our modern understanding of the region. Despite the advent of satellite imagery, GPS, Lidar, Gigapans, drones and other modern tools, his maps and observations stand the test of time.

Early Life Through Completion of Master’s Degree

King was born in Indiana but moved to Iowa City as a boy of five in 1908, following his father who was Professor of Psychology and Education. He describes his life up until High School as “miserable” due to bullying, as he had no aptitude for sports and was viewed as an introspective and bookish “stuck up professor’s boy”. His father possessed an amateur interest in geology and was friends with Samuel Calvin, whose fossil collection King envied. Unhappy with lack of promotion, King’s father left the university during WWI to work a civilian job with the YMCA and was often away from home, creating a poor and somewhat unsettled childhood.

King graduated from University High School (Iowa City) in 1920. Despite modern confusion, he received his BS (1924) and MS (1927) from what is now the University of Iowa in Iowa City, at the time called State University of Iowa, leading some sources (e.g. Wikipedia) to incorrectly assign his alma mater as Iowa State University (Ames, IA). He went on to receive his Ph.D. from Yale in 1929.

Upon entry to university life as a freshman, King described himself as “poor, shabby, and friendless” with “few social graces”. One of his freshman courses was Geology in Old Science Hall (now Calvin Hall). The Geology faculty all came from the University of Chicago, the leading Midwestern institution of the day, and included George F. Kay (Head of Department, Dean, and State Geologist whom King described as “a stuffed shirt” mainly interested in banning smoking from the building), Arthur Trowbridge (“a truly dynamic guy”), Abram O. Thomas, Ralph C. Cheney (who left soon after for Berkeley where he attained distinction), and Joseph J. Runner (“jolly and outgoing, quite a contrast with the rest of the department, and something of a maverick; he shocked them all by talking seriously about continental drift”). C.K. Wentworth was an Instructor, famous for publishing the Wentworth Scale for grain size classification in 1922. Wentworth invited sophomore King to attend his first field geology course at Baraboo, WI. Wentworth “was a hard taskmaster” and “odd duck” who eventually gave King a ‘B’ grade, “which was very generous of him”. As a junior, King learned plane-table surveying, also from Wentworth. In addition to Geology, King took 3 years of art classes leading him to publish cartoons in a university humor magazine and his senior year Hawkeye yearbook. His artistic skill is evident in his classic geology publications, which are renowned for accurate field sketches. Socially the small group of art students became “the only real attachments” he made at university.

Starting junior year, Prof. Runner took King under his wing and gave him an assistantship sorting out the department’s mineral collection. That summer King worked as Runner’s assistant on a consulting job in North Dakota, after which he visited Yellowstone Park, followed by Runner’s field geology course in the Black Hills. This was his first taste of “the Great West” and the beauty of the country entranced him. Returning “starry-eyed” to Iowa City he found it very dull by comparison. In his senior year, he took Advanced General Geology from Prof. Trowbridge. Although in retrospect he felt some of the teachings were “manifestly wrong”, the advanced study of topographic and geologic maps firmed up his interests, and “Few young geologists in other schools ever got such rigorous map training.” Marshall Kay, son of Dean George Kay, also took the class. Marshall went on to fame integrating tectonics and stratigraphy at Columbia University, and is often associated with pre-plate tectonic Geosynclinal theory. King presented his first scientific paper as a junior to the Iowa Academy of Sciences on the topic of physiography of southwestern North Dakota.

King graduated in 1924 as a Phi Beta Kappa and With High Distinction. The Louden prize that year ($10) was split between King and Marshall Kay. Socially, although he had friends in the Art Department, he “…never dated anyone, and did not go to dances or other college affairs.” He took the Geological Survey Civil Service exam and “…passed with a low grade of 73, but no Survey offers were made.” With no job prospects presenting themselves, Prof. Runner again took interest in King by writing to an oil friend in Dallas and getting him a position at Marland Oil Co. as Geological Assistant for $100 per month. Here he purchased the Geologic Map of Texas and noticed that the peculiar area of the Marathon Basin and Glass Mountains did not fit the well-ordered stratigraphic patterns found in the rest of the state. He transferred to West Texas, where he would spend the next year surveying surface structures with alidade, plane table and stadia – “the plane table had a wobble in it and was hard to keep level. We had a Model T Ford which was always breaking down and getting many flat tires.” His social awkwardness continued, “The oil people were a rough crowd, quite different from anything I had been exposed to in Iowa…a carousing, drinking, whoring crowd. They made me the butt of their jokes, but other ‘nice boys’ were also picked on.”

In April 1925, King received a letter from his younger brother, Robert, who was graduating from Iowa with a Bachelor in Geology and looking for a Master’s thesis topic focused on paleontology. P.B. decided to quit the oil business and return to Iowa for graduate school, where he and Robert would work on the geology of the Glass Mountains and Marathon country. The area had newly published topographic maps but only reconnaissance level geology work, “…so the region was ready for geologic mapping”. The brothers began the daunting task of mapping the exceedingly complex thrust-faulted terrane of the Marathon region. While mapping, he met a group on their summer field course from the University of Texas led by Prof. Whitney, and he shared his mapping results.

After a full summer of mapping, P.B. returned to Iowa City in the fall of 1925 to begin his Master’s work. He took classes and had a graduate assistantship helping with the Geology 1 course. Although King worked hard, he “…didn’t seem to accomplish much – later, I was to characterize it as ‘furious lost motion’. I was much discouraged, but soon my fortunes were to take a dramatic turn for the better. Toward end of October, I received an amazing letter from Prof. Whitney offering me a job as Instructor at University of Texas at $1,800 per year.” The Iowa faculty permitted King to leave after Christmas, “They were much surprised…because it was unheard of that anyone should get an Instructorship when he did not even have a Master’s degree…”. In Austin, King spent much of his time at the Bureau of Economic Geology (also housed on campus), and became friends with Bureau geologist John T. Lonsdale, a fellow University of Iowa graduate. King “blossomed out” in Texas, leading many local field trips and working with the famous paleontologist Charles Schuchert of Yale who was in Austin as visiting professor. Schuchert was interested in the Glass Mountains region after his own visit there a number of years before determined it was a critical section to understand the Permian of North America. Schuchert wanted Robert and P.B. to continue their work and go to Yale for Ph.D.’s. He agreed to buy all of Robert’s Glass Mountains paleontology collection for the Peabody Museum. “Up to then, I had no further plan than to get a Master’s degree at Iowa; I had never conceived of the idea of getting a doctorate at one of the famous schools in the East. So – Robert was to go to Yale the following fall, and I would follow next year, when I finished my work at the University of Texas. Financing of further work in the Glass Mountains would come from a subsidy from Professor Schuchert for the fossil collections, and from expenses that had been arranged by Schuchert from the Bureau of Economic Geology.”

For the 1926 field season P.B. and Robert based themselves in Alpine and Marathon, TX for further work on the Glass Mountains/Marathon region. They took side trips to Carlsbad Caverns and the Guadalupe Mountains, as well as the Sierra Diablos north of Van Horn – areas King would work in detail the following years. Mapping went well, and “At the end of the season we drove back to Austin, and we both took the train back to Iowa City, I for a short visit, Robert to go on to Yale, for his first year.” Returning to Austin for his second semester as Instructor, King worked up the Geomorphology of the Glass Mountains and Marathon Basin for his Master’s thesis at Iowa. “At Christmas, I went north by train to Iowa City, and Robert came back from New Haven…I brought along my manuscript…and submitted [it] to the Geology Department for a Master’s thesis. The Department gave me some written and oral examinations, and I was given my M.S. degree…”

Ph.D. and Brief Synopsis of Later Life

Much of King’s work at Yale built upon the fieldwork he had begun as an Iowa student. The 1927 field season included mapping the Sierra Madera hills which were “greatly confused, smashed, and jointed, and hence hard to understand...”. The feature was later determined to be an impact structure, and although not interpreted as such by King, it was correctly mapped. The Glass Mountains geologic mapping was completed at the end of the 1927 field season, after which King headed east to New Haven to begin at Yale.

P.B. and Robert moved their mapping area north in 1928 to the Hueco Mountains, where they “…found a prominent angular unconformity at the base of the Permian…and to our surprise found that the Permian beveled all the older formations southward…” It is now established this unconformity is part of the Marathon-Ouachita tectonic event that formed the foreland Permian Basin, and is visible in outcrop and seismic throughout the region. After finishing the Huecos, they set up doing fieldwork in the Sierra Diablos. In 1929, P.B. finished his dissertation and went back to map the Marathon Basin area for the USGS on a temporary assignment. Any future employment was uncertain, but in the fall of 1929, he was offered a 1-year Instructor position at the University of Arizona teaching Introductory Geology. In June of 1930, he was back in the Marathon Basin working for the USGS, this time a permanent hire with an office in Washington D.C. King married his wife, Helen, in 1932. His last major West Texas mapping project (done without his brother Robert, who entered the oil industry) was the southern Guadalupe Mountains, with most of the fieldwork completed over eight months in 1934-1935 and publication in 1948.

King had no great love for Iowa City and returned only sporadically through the 1930’s to visit family. Some of this thoughts on Iowa include: “I have wondered how any one in Iowa City could have been interested in the subject [of Geology], for it was a most uninspiring locale – a terrane of dissected Kansan loess, without any distinguishing features of any kind…In spite of its uninspiring surroundings, the Iowa department turned out many geologists, nevertheless, most of whom went into petroleum geology, and many of whom distinguished themselves later…Possibly some of them, like me, found geology as a means of getting away from the dull scenery and people of Iowa, into more exciting regions.”

In 1937, he returned to Iowa City for his father’s funeral, and during a 1938 visit saw his mother for the last time. In 1939, he spent a month in Iowa City to deal with affairs and close up the family house. “While there, I did what I could on the family estate…father’s affairs were somewhat tangled. Much of my time was spent with Art Miller and Bill Furnish on the Permian, whose ammonoids they were working up into a monograph. In the evening, Art and Bertha Miller took us sometimes to the Amana Colony about 12 miles west of Iowa City, where we ate lavish German dinners. We also spent a day…at Lake McBride, a reservoir that had been built since my day…Finally, we packed up to go east, and I left Iowa City, never to return.”

King would go on to look for strategic minerals during WWII in the Appalachia region, work that would expand to extensive geologic mapping that would take up much of his later career. In addition, he synthesized the Tectonic Map of North America (1969) and the Geologic Map of the United States (1974). In 1965 he was awarded both the Penrose Medal by the Geological Society of America and the Distinguished Service Medal by the U.S. Department of Interior, and in 1966 was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He held temporary teaching assignments at the University of Texas, University of Arizona, UCLA, and the University of Moscow. He died in 1987 at the age of 83 in California, having retired from the USGS at age 69.

After retiring, King wrote an autobiography from which most of the material in this article was summarized, it is available through the USGS at:

https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2000/of00-443/of00-443.pdf

Selected major works

- King, Philip B., 1937, Geology of the Marathon Region, Texas, United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 187, 148 pp.

- King, Philip B., 1948, Geology of the Southern Guadalupe Mountains, Texas, United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 215, 183 pp.

- King, Philip B., 1959 revised edition 1977, The Evolution of North America, Princeton University Press

- Tectonic Map of the United States (1944; 1962; 1989)

- Tectonic Map of North America (1969)

- Geologic Map of the United States (1974)